The primary function of the canine and feline urinary system is to excrete waste products from the body. Therefore, the health of the urinary system is critical for the health of all of the body’s other systems. Understanding and maintaining your pet’s urinary system is essential to their overall health. In this article, we’ll cover the organs and functions of the urinary system, as well as the common diseases of the urinary system (and their symptoms) and how the vet can diagnose them.

Organs of the canine and feline urinary system

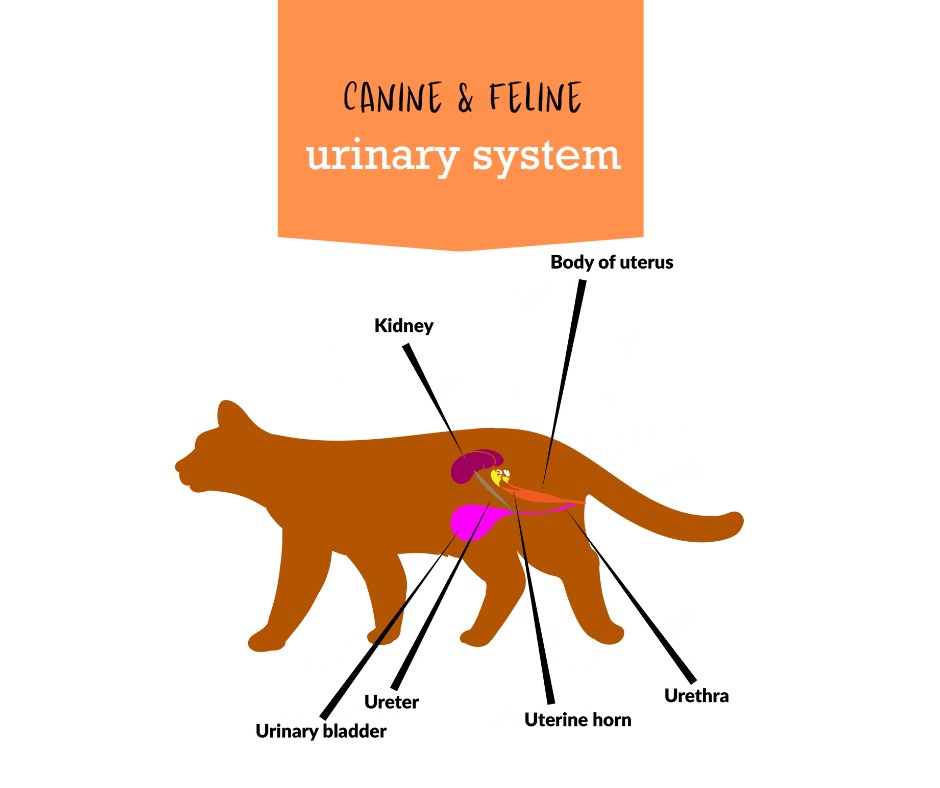

Canine and feline urinary systems are very similar in structure, and consist of the following organs:

- kidneys

- ureters

- urinary bladder

- urethra

The kidneys are responsible for filtering waste materials out of the blood, balancing the body’s electrolytes and water (to maintain hydration), controlling blood pressure, assisting in red blood cell production, and assisting in the metabolism of calcium.

The ureters are the two tubes that connect the kidneys to the bladder.

The urinary bladder collects and stores urine until the dog or cat is ready to urinate.

The urethra is the tube that transports urine from the bladder to outside the dog or cat’s body. Males and females have different urethral lengths and diameters, which we’ll explain below.

Functions of the canine and feline urinary system

The canine and feline urinary system has a number of essential functions:

- excretion of waste products that accumulate from digestion and metabolism

- excretion of toxic substances, to reduce toxicity in the body and restore health

- water and electrolyte balance in the body

- production of the hormone erythropoietin and the enzyme renin, which maintain blood pressure and sodium levels in the blood

- metabolising vitamin D and converting it to calcitriol (the most active form of vitamin D)

- regulating the body’s pH levels (acid-base balance)

How does the canine and feline urinary system work?

The kidneys, situated in the abdomen (near the spine towards the tail), are each made up of three main parts:

- the cortex (outer layer)

- the medulla (beneath the cortex)

- the renal pelvis (within the kidney)

The cortex is responsible for filtering the blood and it is here that urea and other biological waste products are filtered, collected, and combined with water to form urine. The urine is then sent to the renal pelvis where it accumulates before travelling through the ureter (one from each kidney) to the urinary bladder.

The ureters are very narrow fibromuscular tubes that feed urine to the bladder through peristaltic motion. Feline ureters are extremely narrow (around 0.4 mm), while large breed dogs’ ureters are wider (around 2.5mm). Feline ureters are thus more prone to obstruction from uroliths (kidney stones – we’ll discuss below).

The urinary bladder is like an expandable balloon of muscle that collects urine via the ureters until it’s full enough to be released. When the bladder is full, sensory nerve cells in the wall of the bladder alert the animal’s brain that they need to void it. The bladder sphincter is a voluntary muscle that keeps urine within the bladder until it’s full enough to be released. When the animal relaxes the sphincter, the urine exits the bladder via the urethra.

The urethra is the tube that connects the bladder to the external environment, giving the urine a pathway to the outside. Male dogs and cats have a long, narrow urethra; females’ urethras are shorter and wider.

As the dog or cat’s body is in a constant state of metabolising resources (food, oxygen, etc.) and producing waste products, the urinary system is always working in order to maintain homeostasis in the body.

When should you contact the vet about your pet’s urinary system?

When your pet’s urinary system is working properly, the colour of their urine will be on a spectrum of transparent yellow to pale gold or amber. They will urinate regularly throughout the day in the spot they’ve been trained – for dogs, that would be outside on the grass, and for cats, either outdoors or in their designated litterbox.

If you notice a change in your pet’s elimination habits, it’s advisable to contact the vet immediately for a check-up, as any changes in urinary habits and composition can indicate a more serious problem. Changes could include:

- straining to urinate

- very dark urine or brown or pinkish urine (indicating blood in the urine)

- very obvious blood in the urine

- urinating in inappropriate places, especially if already house-trained or litterbox-trained

- increased thirst

- urinating in larger quantities than usual

- urinating more frequently than usual

- increased licking of the genitals after urinating

If your pet strains to urinate and produces no urine, or does not attempt to urinate for 24 hours, this is a medical emergency and you must contact the vet immediately.

How the vet diagnoses problems in your pet’s urinary system

Your pet’s urine can tell the vet a lot about your pet’s health. The vet will perform a physical examination on your pet and may ask you questions about your pet’s behaviour leading up to their possible urinary system disorder. They will want to know about changes in their water consumption and elimination, as well as the volume of urine; whether there have been changes in your pet’s diet, medication and body weight. The vet has a number of tests to perform to determine whether something is going on with your pet’s urinary system. These may include:

Urinalysis

When the vet examines your pet’s urine sample, they can look for substances that should and should not be in the urine. Abnormal substances will include blood, sugar, proteins, and white blood cells. They can also evaluate whether there is too much or too little water (urine concentration), which will indicate whether the kidneys are functioning as they should. Urinalysis offers a unique look at your pet’s health, and gives the vet a great starting point to further explore what may be affecting your dog or cat.

If the vet suspects an infection in the urinary system, they will perform a bacterial urine culture to confirm the infection and determine which course of antibiotics to prescribe.

Blood tests

Hand-in-hand with urinalysis, blood tests can also give the vet insight into what’s going on in your pet’s body. Blood and urine tests are complementary to each other because the presence of certain markers in the blood (from a biochemical profile) can correlate with what is found in the urine, and show whether the kidneys and other urinary organs are functioning as they should.

Blood pressure test

Blood pressure testing can also offer valuable insight into the health of the kidneys, as it’s the kidneys that balance water and electrolytes. If the kidneys are diseased or failing, this will show in the blood pressure reading.

Diagnostic imaging

X-rays and abdominal ultrasound may reveal changes in the size and shape of the urinary organs, the presence of uroliths or calculi, as well as detecting whether an infection in the urinary system is located in the upper or lower urinary tract.

Surgical exploration

In cases where the vet suspects a particular urinary tract disorder, surgery may be necessary to confirm the diagnosis, perform a biopsy, or to perform corrective therapy while they have access to the urinary structures. Bladder or kidney stones may also be surgically removed – the vet will analyse the mineral content of uroliths to determine how to alter the pet’s diet or medication to prevent the kidney or bladder stones from recurring.

Common disorders in the canine and feline urinary system

Congenital problems in the urinary system are rare for dogs, although a common congenital feline issue is polycystic kidney disease (PKD), which affects almost 40% of cats with Persian origins. Let’s look at some of the more common urinary system issues that affect dogs and cats.

Urinary bladder infection

Urinary tract infections (UTIs) and urinary bladder infections (also called bacterial cystitis) are relatively common in dogs and cats, and are caused when bacteria enter the urinary tract via the urethra. Pets that are unable to empty their bladder completely are more prone to UTIs, which – when not treated promptly – can develop into bladder infections as the bacteria migrate up the urethra and become more established in the bladder.

Symptoms of a bladder infection include more frequent urination, but straining to produce urine. Blood may be present, especially towards the end of urination. Sometimes bladder infections in dogs show no symptoms at all, and are only diagnosed when urinalysis is performed for a different condition or during a routine check-up.

Some pet medications can increase the risk of bladder infections and UTIs, or the infections may be a side effect of another condition such as cysts, uroliths, urinary system tumours, growths or other congenital problems.

Lower urinary tract disease in dogs

Lower urinary tract disease is a diagnosis that covers various issues in the urethra and/or bladder. It can be the result of infection (cystitis) and or inflammation without infection (sterile cystitis). While the same symptoms (straining to urinate, excessive thirst, urinating inappropriately in the house, blood in the urine, etc.) may show up for both, the correct diagnosis is important so that the vet can give the animal the right treatment.

Feline lower urinary tract disease (FLUTD)

Cats are prone to idiopathic feline lower urinary tract disease (FLUTD) (also called feline idiopathic cystitis or feline interstitial cystitis), which is inflammation of the bladder with an unknown cause. There may be a causal link between stress, hormonal influence, diet, viral infection, and even genetics – with both male and female cats equally susceptible to FLUTD.

In many cases, male cats may develop an obstruction in the urinary tract, which calls for emergency treatment. A sign that a male cat may be in distress due to an obstruction includes crying in the litterbox, coupled with appetite loss and lethargy. Unfortunately, this can become a recurring problem, and because there is no known cause, the vet will treat the symptoms and attempt to reduce the recurring episodes. Pain management may be necessary.

Stress reduction is vital for cats that are susceptible to FLUTD, and care should be taken to encourage these cats to drink a lot more water in order to dilute their urine. Switching them to wet food (cans or pouches) can help to increase their water intake. In multi-cat households, each cat should be given their own place to retreat to, their own food and water bowls, and their own litterboxes. This reduces the need for competition for resources, which can be stressful for cats. Calming pheromones and stimulating playtime can also help to reduce or relieve stress, giving cats an environment that is less likely to trigger FLUTD.

Urinary tract obstructions

In dogs, kidney stones are the most common cause of urinary obstruction. When a kidney stone is being passed, it can block the urethra. This kind of blockage can cause a build-up of toxic waste, which then negatively impacts the kidneys. Blockages of the urinary tract can also be caused by blood clots, stones, and tumours. A total blockage, which affects both kidneys, causing them to enlarge, can be fatal to a dog. A partial blockage may not be fatal, but it can damage the kidneys permanently.

The symptoms of a urinary tract obstruction may include:

- small amounts of urine produced frequently

- slow urination

- urination painful enough to elicit crying or whining

- blood in the urine

- painful abdomen

Toxic waste build-up in the blood (caused by the blockage) will have symptoms like:

- vomiting

- dehydration

- lowered body temperature

- painful bladder

- depression

- abnormal heartbeat

Urinary bladder stones

When naturally-occurring minerals in the urine begin to crystallise, these crystals cluster together and form calculi or uroliths – stones of varying sizes – which can be made up of a variety of minerals. These calculi can develop in the kidneys or bladder, but bladder stones are more common than kidney stones in dogs and cats. Very small calculi usually don’t produce any noticeable symptoms, while larger stones in the bladder can severely interfere with the animal’s ability to urinate – causing pain, straining, and blood in the urine.

Urinary calculi are dangerous when they cause an obstruction in the urethra (see above).

It is very rare for dogs and cats to develop kidney stones. If they do, there are seldom symptoms until the stones pass into the ureter/s. If a stone blocks a ureter, it can completely block the flow of urine from the kidney, which can cause permanent kidney damage.

Different calculi or uroliths are composed of different minerals, and their presence will affect different animals in different ways. The treatment and removal of urinary calculi will depend on their composition and location, which the vet will analyse to help to prevent a recurrence. Urinary stones develop under conditions of chronic infection, metabolic changes or defects, and the secretion of excess salts. The pets’ diet, supplements, water intake, urine volume, medication and even simple genetics can influence the formation of calculi. If the vet knows under what conditions the urinary stones develop, they can change the animal’s diet and medication to create a urinary environment that is hostile towards the formation of calculi.

Urinary incontinence

Urinary incontinence occurs when a dog or cat cannot hold their urine and it leaks involuntarily due to a weak bladder sphincter. It is more common in spayed female dogs than female cats, and more common in females than in males of both animal types. Low oestrogen is a common cause of urinary incontinence, but it may also be caused by medication, urethral obstruction, and injuries where the spinal nerves are affected.

Chronic kidney disease and renal failure

Certain cat breeds are prone to congenital kidney disorders, which can damage the kidneys over time. Chronic kidney disease progresses slowly, taking months or even years before symptoms start to show. Dogs can also experience chronic kidney disease because of a congenital problem, but usually it’s the result of old age, with the average onset age being around five or six years old.

Damaged kidneys will not be able to process toxic material from the body, nor will they be able to maintain water and electrolyte balance. Chronic kidney disease usually only becomes apparent after dogs or cats have lost 75% of their kidneys’ function, at which point the vet will only be able to administer intensive treatment to save what little function remains, and not reverse the damage.

Renal failure can be the result of chronic kidney disease or it may be an acute disease resulting from the ingestion of poison or toxic substances. Dogs that are exposed to the ethylene glycol in antifreeze can suffer from acute renal failure.

Kidney infection

A less common urinary condition in dogs and cats is pyelonephritis, or an infection in the kidneys. Healthy pets are unlikely to contract a kidney infection, but very young, very old, and those who are more susceptible to lower urinary tract infections, polycystic kidneys, and calculi are at risk of kidney infection. The bacteria from recurring bladder infections can travel up towards the kidneys and make the animal very sick.

Sometimes kidney infections have no symptoms until they result in renal failure. However, general symptoms of kidney infection include:

- pain near the kidneys

- general unwellness

- fever

- vomiting

- reduced appetite

- excess thirst

- excessive urination

Other less common conditions in the urinary system can include:

- Cancer and/or tumours

- Proteinuria (too much protein in the urine – commonly a sign of kidney disease)

How to take care of your dog or cat’s urinary system

The best way to ensure the whole health of your dog or cat is from the ground up: high-quality, for-purpose nutrition. Feed your pet the right food that has been formulated for their breed, size, age and any health conditions they may have. This will ensure that they are consuming the right amount and ratio of proteins, carbohydrates and fats, as well as the right balance of vitamins and minerals. This is especially important when considering kidney and bladder health, where the right balance between electrolytes and water ensures optimal urinary health; and whether the incorrect ratio of certain minerals can increase the chances of urinary calculi.

Keep your pets properly hydrated. This means they need to always have access to fresh water, preferably from their own bowl if in a multi-pet household. Always monitor your pets’ urination habits – if their habits change, it may be an indication that there is a problem with their urinary system.

Try to reduce stressors as much as possible, and make sure your pets visit the vet regularly to get them checked out.

If you are concerned about the frequency of your pet’s urination habits, the colour, odour or behaviour around your pet’s urination, make a note of your concerns and contact the vet immediately. They will be able to perform a range of tests that will provide insight into your pet’s urinary health.

© 2024 The Code Company